It’s hard to beat the views that come with bicycling around Northern California’s Angel Island, the largest natural island in San Francisco Bay. As my boyfriend Chris and I pedalled along the island’s largely undulating 5.5-mile paved Perimeter Loop, we encountered postcard-worthy vistas around every turn.

At one point, we saw the iconic Golden Gate Bridge stretching between San Francisco and the sage-and-yarrow-covered peninsula of the Marin Headlands; at another, we spotted Angel Island’s more infamous neighbour, Alcatraz Island, where some of the most notorious inmates of the early-to-mid-20th Century served time.

Though I’ve lived in San Francisco for nearly 30 years, I’d only ever visited Angel Island a few times. Compared to the Bay Area’s many other attractions – like Sonoma County’s wineries; the waterfront city of Sausalito, which looks like it popped right out of the French Riviera; and San Francisco’s many eclectic neighbourhoods – Angel Island tends to get overlooked, even by locals. Strange, since it’s absolutely teeming with history, from its days as a US military base to becoming a major immigration centre that processed up to one million people and later a Japanese internment station. In fact, by the time the California State Park system first acquired the island in 1954, this former home of the Indigenous Coast Miwok people had already lived many lives. Add to this 13 miles of hiking trails, paved and mountain cycling paths and 16 campsites adorning a car-free parkland that’s only reachable only by boat, and you’ve got one of the area’s best urban getaways.

To better understand how this one-square-mile isle has shaped the region and nation, we decided to spend a Saturday afternoon touring Angel Island on two wheels. Bringing our bikes, we joined the dozens of others who’d taken the Angel Island Ferry 15 minutes over from the Marin County town of Tiburon, the closest mainland point.

Our ferry docked at Ayala Cove, a historic point named after the Spanish naval officer Juan Manuel de Ayala. In 1775, he and his crew were the first Europeans to sail into San Francisco Bay. In 1891, Ayala Cove became the site of a US quarantine station, where ships arriving from foreign ports were fumigated and any immigrants suspected of carrying contagious diseases such as smallpox and the plague were kept in isolation.

Today, the cove is Angel Island’s main arrival point. It’s home to a cafe where you can pick up beer and wine, soft drinks and snacks, as well as the Angel Island Company that rents mountain bicycles and e-bikes by the hour or day.

We cycled up a sharp incline to the Perimeter Loop, where a rocky terrain brimming with native oak and bay trees, and introduced species like Monterey pine, eucalyptus and Douglas fir awaited us. An occasional red-tailed hawk circled the sky as we cycled past stands of California poppies, encountering fragmented remains of the island’s many former incarnations en route.

The Coast Miwok used Angel Island as a base to fish for spawning salmon, hunt marine mammals and forage for acorns. But the island is perhaps best known for its later military and immigration history.

Angel Island’s strategic location along San Francisco Bay made it an ideal place to establish a military reserve from 1850 until World War Two, and as Chris and I cycled up a hillside, the ruins of crumbling military buildings decorating the island’s east side came into view. A boarded-up hospital remains perched above Camp Reynolds, home to the nation’s oldest standing group of US Civil War buildings, dating to the 1860s.

In 1905, the US military transferred control of 20 acres of Angel Island to the Department of Commerce and Labor in order to establish an immigration station on the US’s West Coast similar to its East Coast counterpart, New York City’s Ellis Island. Between 1910 and 1940, the facility processed up to one million immigrants, most of whom were Asian, leading it to be known as the “Ellis Island of the West“.

As a result of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which prohibited Chinese labourers from entering the US, many of these immigrants – including 85,000 people of Japanese descent who faced indiscriminate Asian racism – were endlessly detailed, enduring interrogations and medical exams, often for no reason other than their nationality. And while most Americans know of Ellis Island’s historical importance as a welcome centre for Europeans, few seem to know about that of its western counterpart, whose geographical proximity to Asia led it to become the major point of entry in the US for Asians.

“I was born in the Bay Area, but my heritage is Chinese,” says Cynthia Yeh, a project manager at the University of California, Office of the President. “I appreciate that Angel Island has postings with information about its history, because it’s a significant history, and not something that I ever learned in school.”

Later, during WW2, the station was used as a processing centre for Japanese and German prisoners of war, and served as a temporary internment centre for 700 Japanese Americans before the US government sent them to facilities further inland.

“Angel Island is one of the most important landing spots in Japanese American history,” says Kenji G Taguma, a Japanese American who’s president of the non-profit Nichi Bei Foundation that aims to empower the Japanese American community. For Taguma, visiting the island means honouring the spirit of the Issei, or first generation of Japanese people to immigrate to the Americas. “They could not have known what was awaiting them here, from racism and discrimination, to forced removal and incarceration during World War Two,” he said. “Yet they persevered. They also really paved the way for generations to come.”

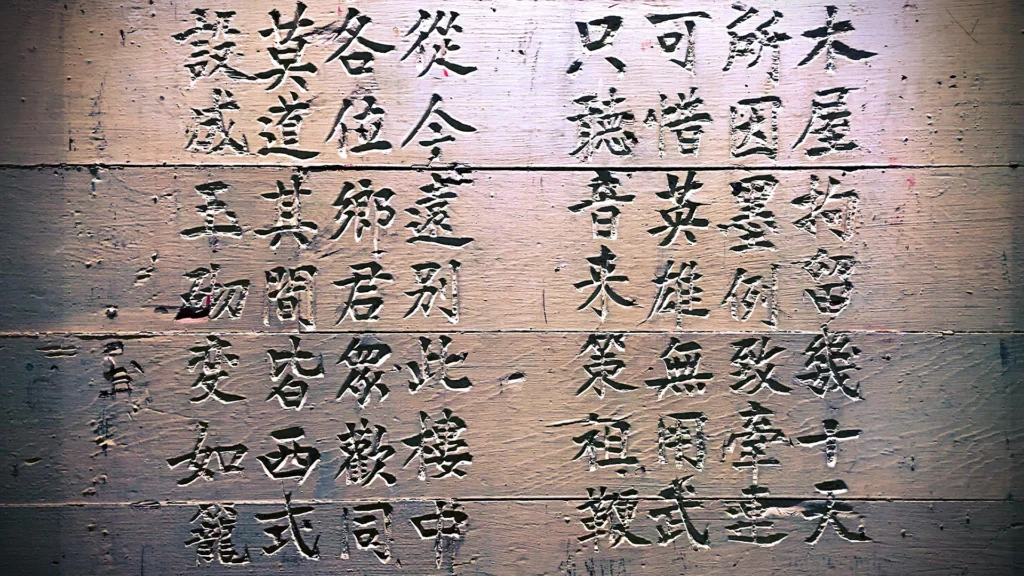

Today, the former immigration and internment centre (a 2.4-mile round-trip hike from Ayala Cove, and slightly longer by bike) houses a museum that highlights the harsh realities of the detention barracks, including Chinese poetry engraved on the walls by those detained here.

Throughout the day, Chris and I stopped to read the many information signs stationed along the Perimeter Loop, each one revealing new details about the island’s long history. We also enjoyed the fact that the dense white fog that often reaches across the bay like giant tendrils decided not to show itself, leaving nothing but pristine blue skies and sweeping views of the San Francisco skyline.

“Let’s pull over,” I said to Chris, motioning toward a sign for Battery Ledyard, the remnants of one of three decommissioned military gun batteries remaining on the island. These reinforced concrete ruins offer one of the most jaw-dropping overlooks of the Golden Gate strait, where San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean meet. They’re also an ideal spot for snapping pictures of the city skyline framed by the island’s rolling meadows, especially during spring, when purple spheres of California lilac perfectly frame each photo’s forefront.

- List of African countries seen as lower-middle income countries

- Top 10 African countries with the highest foreign direct investment

- Top 10 African countries with the highest fuel prices in June 2024

- Top 10 African countries with the lowest fuel prices in July 2024

- Instagram removes 63,000 sextortion accounts in Nigeria

We occasionally encountered groups of other cyclists, or a family sharing snacks at one of the island’s many picnic tables. While we sat watching a sailboat slowly navigate the bay’s cold waters, an open-air tram filled with passengers came around the nearby bend, stopping to allow those on board a chance to stretch and take in the panoramic Bay Area vistas.

Although I’d originally wanted to spend the night on Angel Island, camping here requires some advanced planning. With only 16 primitive campsites split between four locations, reservations fill up quickly and often have to be booked months in advance – especially covered sites like numbers four and five at Ridge Camp. Like the island’s other camping spots, they’re hike-in only, but within easy distance to Battery Ledyard, they offer some of its most spectacular views. The trade-off is the wind, which can drop temperatures substantially at night.

One of the island’s most strenuous – though rewarding – hikes is its Sunset Trail, a more-than-three-mile route that includes 800ft of elevation gain from Ayala Cove. It tackles the landmass’s tallest peak, 788ft Mount Livermore, which gives Angel Island its pyramidal shape. The summit is named for Caroline Livermore, a Bay Area conservationist who was instrumental in protecting the island from development in the mid-20th Century, paving the way for it to become a California State Park. Its unobstructed views of both San Francisco and Oakland in the East Bay are breathtaking reminders of how easy it can be to get away, while barely leaving the city.

Chris and I were so lost in the scenery that we missed the last ferry back to Tiburon. It could have been a costly mistake since the only other way off the island requires chartering a private boat, but thankfully we made it just in time for the final San Francisco ferry.

Our snafu tacked on another 18 miles of cycling to return to Tiburon, but I was surprisingly up for the challenge. Given the island’s long and difficult history, the freedom for anyone to come and go as they please was a reminder of how far we’ve come.